“You have to understand

That no one puts their children in a boat

Unless the water is safer than the land” – Warsan Shire

Across the world, millions of people are fleeing the ravages of war and internal conflict, only to find themselves in unfamiliar territory with little to no support. By the time a refugee or asylum seeker has landed in Australia, he or she has undergone immense physical, psychological, and financial hardship. Much of the onus falls on doctors and other healthcare providers to engage with these individuals and help them piece together what they have lost along the way.

In 2014, the number of globally displaced persons was 59.5 million, a figure that is projected by this year to reach an all-time high [1]. It is estimated that one person out of every 122 in the world is fleeing home for fear of persecution or death [2], an alarming indication of the scale of what can accurately be called a global crisis. A subsequent increase in resettled refugees is expected in Australia [3,4], which will create the necessity for a healthcare system that is prepared to address the needs of such a uniquely vulnerable population. Although adequate healthcare is a crucial component for the restoration of refugees’ lives, access to essential healthcare services and medicines has been particularly restricted in this demographic [5-7]. As general practitioners (GPs) are often the first port of call for refugees with health needs, the strengthening and monitoring of primary healthcare programs have been identified as key areas for improvement by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) [8] and by local health authorities [9]. GPs have a unique platform to bring refugee rights into daily discourse and advocate for their right to equal and affordable healthcare. This article aims to provide a brief introduction to the common health concerns faced by resettled refugees in Australia, barriers in terms of access to essential care and medications, and ways in which GPs can improve their service provision to refugees.

Common health concerns of refugees and the importance of intervention

Physical health

The compromised wellbeing of newly resettled refugees is the result of a combination of factors. These include interrupted or reduced access to healthcare before departure; prolonged exposure to harsh environments; and reduced access to basic needs, such as clean drinking water, food, shelter, education, and safety. These may be exacerbated by trauma and extended periods of deprivation, particularly if in detention [9]. Tuberculosis, hepatitis B, and intestinal parasitic diseases all occur more frequently in refugees than Australian-born residents and may complicate chronic conditions and undernutrition, which are often overlooked [10]. Refugees commonly have poor dental and optical health and are incompletely vaccinated [10,11]. Anaemia and iron deficiency are also extremely common and have been found in 10-30% of refugee children in Victoria, frequently accompanied by low vitamin D, B12, and folate levels [11].

Unfortunately, another common occurrence among refugees is the presence of the physical effects of torture and trauma. It is predicted that approximately 35% of the world’s refugees have had at least one experience of torture [10]. Patients may exhibit signs and symptoms of chronic pain, amputation of body parts, disfigurement, poor mobility, reduced hearing, and urogenital complications [12]. A further 125 million women and girls in the world are estimated to have been subjected to female genital mutilation (FGM), which greatly increases the risk of pelvic infections, menstrual blockage, sexual dysfunction, pain, secondary infertility, and complications of childbirth [13].

Mental health

Psychological trauma amongst refugees may be the result of a number of influences, including, but not limited to: violence and torture; deprivation; upheaval; and separation from, and loss of, loved ones. These commonly result in feelings ranging from guilt and shame to helplessness and anger, which often endure post-resettlement due to experiences of discrimination and hostility in their host communities and knowledge of the continued hardship of friends and family abroad [14]. Uncertainty about the future is another prevailing sentiment that inhibits the rehabilitation of many refugee families, particularly those on temporary protection visas, which expire within 3 years [15]. Refugees undergoing resettlement have an increased risk of poor mental health [14]. Although a 2008 systematic review of refugee mental health in Australia identifies that the time course of symptomatology varies greatly, a dose-response relationship between the severity of mental illness and the level of trauma experienced is consistent [16]. The conditions encountered are both complex and diverse, and include syndromes, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder, anxiety, depression, somatisation, bereavement disorders, and anger reactions [16,17].

Psychiatric conditions in young people are of particular concern, as children make up more than 40% of newly arrived refugees and are particularly vulnerable to the pressures of upheaval and the stresses that accompany a journey to unfamiliar territory [6,10]. Prolonged periods of detention lead to the arrest or delay of developmental milestones, sometimes creating long-term issues in terms of behaviour, physical wellbeing, and mental health [6,10]. These are complicated by the adverse effects of detainment on parenting and family relationships [18]. Furthermore, adults often underestimate the prevalence and degree of trauma in their children and are frequently suspicious of external help [6].

Entitlements and accessibility

Given the extensive list of health needs that individuals from refugee-like backgrounds are likely to have, access to healthcare services becomes a key issue in disease management. However, several external and intrinsic factors undermine the equity of healthcare provision in this population.

Visas and entitlements

Resettled refugees and asylum seekers have reduced access to health care, in comparison to the majority of Australian residents [4-7]. This is due to a combination of institutional restrictions on entitlements and a number of cultural, economic, and linguistic obstacles experienced by the individuals. Entitlements are established by the type of visa under which the refugee has entered the country. Those who have formally sought and gained international protection are categorised as refugees and therefore, may be granted a Permanent Protection Visa (PPV) under the government-funded Offshore Humanitarian Reclamation Program [19,20]. The PPV, much like permanent residency, permits access to Medicare, a healthcare card, the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS), work rights, and income support, along with services pertinent to their status as refugees, such as an initial health assessment and an early intervention program. Initial health assessments are conducted in primary care settings in most states of Australia, providing invaluable opportunities for the screening and engagement of individuals in the Australian healthcare system [10]. However, patients are only eligible for initial health assessments within the first 12 months of their resettlement [21].

Those who seek international protection but have not been granted the authority to enter another country are called asylum seekers. Asylum seekers who arrive without permission in Australia are placed in detention and may remain there for several years with few rights and little advocacy. A small percentage will be given Temporary Protection Visas (TPVs) lasting three years or less [22]. These come with work rights and Medicare assistance, as well as an initial health assessment; however, they are not eligible for other benefits, such as free settlement services, job assistance, or HECS support. Consequently, non-PPV holders rely heavily on volunteer-run and community-based services and networks. Despite these options, the detrimental psychological effects of uncertain migration status and reduced amenities are well-documented amongst these visa holders and can adversely affect their ability to cope [10,22].

Communication and cultural competence

By far the greatest barrier to satisfactory healthcare is that of communication, which affects access at every level, from first contact with a primary practice through to treatment and follow-up [7,9]. Available interpreting services are under-utilised (particularly by specialists), largely due to the extra time required in a consultation. However, it has been documented that the exclusion of this service leads to reduced patient satisfaction and quality of care [23]. Children or other family members are often used instead, causing ethical concerns that children may incorrectly interpret information that they cannot understand and may even be disturbed by the consultation’s sensitive nature [6]. On the other hand, children may also choose to censor or willingly leave out vital information.

Cultural differences also contribute strongly to difficulties in communication and should be addressed as a potential cause of misapprehension. One Australian study involving 76 GPs revealed that almost 50% of participants were confident in handling refugee cases despite having little or no experience in this area [24]. This is contrary to the pool of data highlighting the difficulty that refugees have in opening up to, and being heard by, health practitioners and other figures of authority in their settlement countries [6,25]. It is therefore important to recognise that deficiencies in cultural competence do exist and can affect patient outcomes despite any obvious signs of this.

Education and health literacy

Limited knowledge of health and healthcare systems is another factor restricting the full utilisation of services by refugees [26]. This may be due to the existence of a very different healthcare system in their countries of origin, or the interruption of health education due to oppression and upheaval [7]. Health literacy and the understanding of the need for the prevention and treatment of asymptomatic conditions are particularly important points to consider when educating a patient, and should be assessed to ensure that self-management is carried out appropriately [7].

Cost

Yet another consideration when dealing with refugee families is the often debilitating cost of relocation and unemployment, and the implications for access to some health services [6,10]. Refugees are often unwilling to use non-Medicare covered dental, allied health, and specialist services, and may face several added restrictions in the form of a lack of transport and unfavourable waiting times [6,25].

The role of primary care and available strategies

Consultation and health screening

General practitioners should make full use of the first contact they have with refugees, as there is no guarantee that the patients will be seen again in the same practice. GPs should keep in mind that initial health assessments are only available to refugees who arrived in Australia less than 12 months ago, and so should encourage eligible patients to undertake them as early as possible [21].

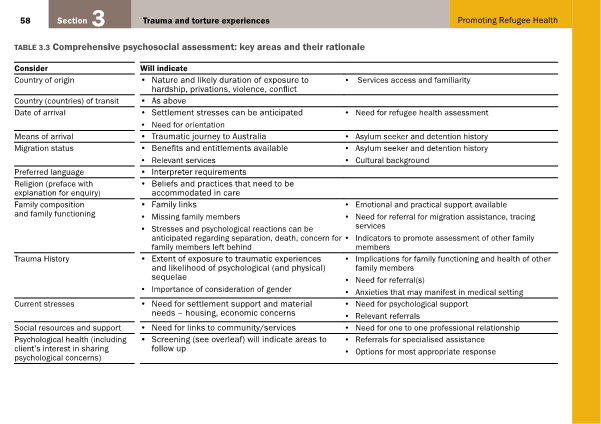

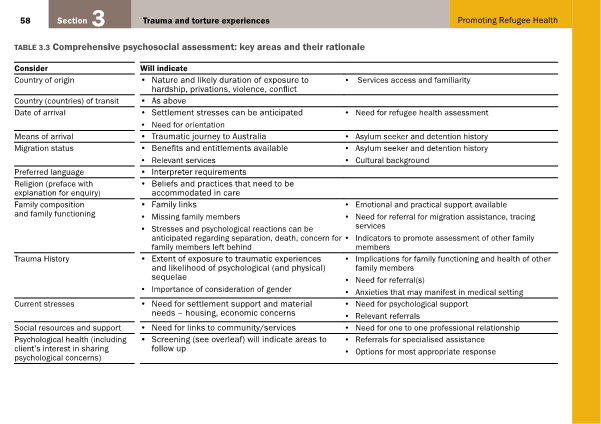

Mental illness makes a large contribution to the disease burden experienced by refugees. It is therefore of utmost importance to adequately screen for sources of psychosocial distress during the consultation. Table 1 is a comprehensive psychological assessment created by the Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture Inc [10] and is useful for this purpose.

Table 1: Comprehensive psychosocial assessment: key areas and their rationale. From Promoting Refugee Health: a guide for doctors, nurses and other health care providers caring for people from refugee backgrounds. Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture Inc [10]. Reproduced with permission.

Murray et al. [14] encourage a social model of treatment that involves families and the community in the management plan of individuals with psychosocial issues. This method has been found to be highly effective and may play a part in reducing stigma, increasing mental health service utilisation, and adding cultural significance to a patient’s journey through the healthcare system. Communication between community networks and local general practices should therefore be nurtured and maintained. The use of bilingual written material and multimedia have also proved to be helpful and encourage patients to approach their healthcare providers with further questions and concerns [25].

Communication

GPs should also be aware of the free Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National), as well as the poorer outcomes observed from its omission from consultations [23]. Care should be taken to ensure that the interpreter is politically, culturally, and socially acceptable to the patient and his or her family [6]. The provision of gender-sensitive consultations has produced further improvements in patient outcomes [25]. As with any consultation, doctors should get a complete idea of each individual’s understanding and expectations of their symptoms, illness, and treatment [7]. A thorough history will also determine the barriers to access of treatment for different patients. Referral to refugee support networks can connect patients with less costly or pro bono health and social services, which are particularly helpful for temporary visa holders, who are not eligible for government-funded health programs [25].

Education and training

In 17 different studies, cultural sensitivity training resulted in an increase in patient satisfaction, reporting of symptoms, referrals, health, and access [25]. Bridging the cultural gap can thus prevent valuable missed opportunities for appropriate care and health promotion. However, if unsure about any aspect of the interaction, Bellamy et al. [7] encourage doctors to ask patients how this aspect of the consultation is usually performed in their home countries. This not only displays respect but also allows the patient to feel accepted, and in return may inspire the acceptance of Western practices.

Referral and follow-up

It is always ideal to maintain a relationship of continuing care with one’s patients; however, refugees in their first few years of resettlement will likely relocate several times, making follow-up unfeasible. To facilitate a smoother transition for these patients, GPs should provide them with hardcopies of all their medical records. When making referrals to services such as pathology, radiology, and allied health, GPs are encouraged to call beforehand to ensure that the practices are open to using interpreting services and to prepare them for patients with special needs [10].

Advocacy

Those who have direct contact with refugees have the unique privilege of seeing these groups at their most vulnerable, and often do not face the same time lag that is experienced by research and the media. This gives them the knowledge and credibility to take early action in the support of refugees in their local communities. Health professionals may consider writing to Members of Parliament and Parliamentary Committee Chairs about these issues. The Refugee Council of Australia (RCOA) is the umbrella refugee organisation in Australia and provides some useful information on methods of contact and communication with policy makers [27,28]. Those who choose to voice their concerns directly with the media must maintain patient privacy and informed consent, as many refugees may be put in grave danger if their identities and locations are revealed [27]. Several local organisations also regularly campaign for refugee rights; membership of these committees may open doors for further advocacy and activism.

Table 2 provides a brief summary of recommendations and resources for GPs who find themselves managing a patient from a refugee-like background.

| Issue |

Recommendations |

Resources |

| Communication and cultural competence |

- Use of translating services and patient education

|

- Atkin N, 2008 [23]

- Australian Government Translating and Interpreting Service [29]

|

- Cultural sensitivity training and further education

- Gender-sensitive consultations

|

- ACEM E-learning courses [30]

- RACGP E-Learning course 22305 – Refugee Health [31]

- Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture Inc. courses and education [32]

|

- Family Planning Victoria, 2012 [12]

|

| Medical problems |

- Initial health assessment

- Adequate history and examination

|

- Australian Family Physician, 2016 [21]

- Victorian Refugee Health Network [33]

|

| Psychosocial problems |

- Adequate psychosocial assessment

|

- The Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture Inc., 2012 [10]

|

| Education and health literacy |

- Use of bilingual reading material

- Patient education and counselling

|

- Victorian Refugee Health Network [34]

|

| Follow-up and referral |

- Provide copies of medical records

- Use of appropriate referral services

- Call beforehand

|

- National Directory of Asylum Seeker and Refugee Service Providers [35]

- Victorian Refugee Health Network [33]

|

| Advocacy |

- Contact with policy makers and media

- Activism

|

- The Refugee Council of Australia [28]

- Refugee Action Coalition Sydney [36]

|

Conclusion

It is evident that providing appropriate and accessible refugee healthcare is a multifaceted task that requires the co-operation of a diverse team of skilled and dedicated professionals. The health of refugees is intrinsically linked to their migration status, education, culture, family situation, and the kaleidoscope of experiences that have landed them in their current situation. General practitioners have a central role in engaging these individuals in health care and the wider community. They must strive to use their position in society to advocate for this underprivileged group and educate resettled refugees on their rights and privileges in their new homes, thus upholding the very pillars of beneficence, autonomy, and justice that encompass the practice of medicine.

Acknowledgements

None.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

[1] Kotschy G. UNHCR Mid-Year Trends 2015. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; 2015:3-13.

[2] Gaynor T. 2015 likely to break records for forced displacement – study [Internet]. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; 2015. Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/5672c2576.html

[3] World Report 2015: Australia [Internet]. Human Rights Watch; 2015. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2015/country-chapters/australia

[4] Wright B. Asylum seekers and Australian politics, 1996-2007 [PhD thesis]. University of Adelaide, School of History and Politics; 2014.

[5] Murray S, Skull S. Hurdles to health: Immigrant and refugee health care in Australia. Aust Health Rev. 2015;29(1):25-9.

[6] Davidson N, Skull S, Burgner D, Kelly P, Raman S, Silove D, et al. An issue of access: Delivering equitable health care for newly arrived refugee children in Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2004 Sep 1;40(9‐10):569-75.

[7] Bellamy K, Ostini R, Martini N, Kairuz T. Access to medication and pharmacy services for resettled refugees: A systematic review. Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21(3):273-8.

[8] Bhattarai S. The UNHCR Global Appeal 2014-2015: Providing for Essential Needs. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; 2014.

[9] The Victorian refugee and asylum seeker health action plan 2014-2018. Department of Health; 2014.

[10] Promoting refugee health: a guide for doctors, nurses and other health care providers caring for people from refugee backgrounds. 3rd ed. Brunswick: Foundation House – The Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture Inc.; 2012. Table 3.3 Comprehensive psychosocial assessment: key areas and their rationale, p.58.

[11] Immigrant Health Service: Overview of health issues in immigrant children [Internet]. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne; 2015. Available from: http://www.rch.org.au/immigranthealth/clinical/Overview_of_health_issues_in_immigrant_children/

[12] Improving the health care of women and girls affected by female genital mutilation/cutting: a service coordination guide. Family Planning Victoria; 2012.

[13] Female genital mutilation/cutting: a statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change. UNICEF; 2013.

[14] Murray K, Davidson G, Schweitzer R. Review of refugee mental health interventions following resettlement: Best practices and recommendations. Am J Orthopsychiatr. 2010;80(4):576-85.

[15] Harris M, Zwar N. Refugee health. Aust Fam Physician. 2005 Oct;34(10):825-9.

[16] Murray K, Davidson G, Schweitzer R. Psychological wellbeing of refugees resettling in Australia: A literature review prepared for the Australian Psychological Society. Australian Psychological Society; 2008.

[17] Srinivasa Murthy R. Mass violence and mental health – Recent epidemiological findings. Int Rev Psychiatr. 2007 Jan 1;19(3):183-92.

[18] Silove D, Austin P, Steel Z. No refuge from terror: The impact of detention on the mental health of trauma-affected refugees seeking asylum in Australia. Transcult Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;44(3):359–93.

[19] Australia’s Offshore Humanitarian Programme: 2013-2014. Department of Immigration and Border Protection; 2014.

[20] Guide to social security law: 9.1.2 Visas issued by DIBP [Internet]. Australian Government; [updated 2014 November 10; cited 2016 Jan 4]. Available from: http://guides.dss.gov.au/guide-social-security-law/9/1/2

[21] Benson J, Smith MM. Early health assessment of refugees. Aust Fam Physician. 2007 Jan;36(1-2):41-3.

[22] Policy Brief: Temporary Protection Visas. Refugee Council of Australia; 2013 Sep 24. Available from: http://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/r/pb/THC_140206.pdf

[23] Atkin, N. Getting the message across: Professional interpreters in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2008 Mar;37(3):174-6.

[21] Duncan G, Harding C, Gilmour A, Seal A. GP and registrar involvement in refugee health: A needs assessment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013 Jun;42(6):405-8.

[25] Joshi C, Russell G, Cheng IH, Kay M, Pottie K, Alston M, et al. A narrative synthesis of the impact of primary health care delivery models for refugees in resettlement countries on access, quality and coordination. Int J Equity Health. 2013 Nov 7;12(88):1-4.

[26] Cheng I, Wahidi S, Vasi S, Samuel S. Importance of community engagement in primary healthcare: The case of Afghan refugees. Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21(3):262-7.

[27] Cugati A, Lurie C, Piper M. The Advocates’ Help Kit. Refugee Council of Australia; 2002 Dec:10-31. Available from: https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/docs/resources/VIC_ADVOCACY%20KIT.pdf

[28] Contacting Politicians: Letter Guide [Internet]. Refugee Council of Australia. Available from: http://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/take-action/contacting-politicians/

[29] The Translating and Interpreting Service Website [Internet]. Australian Government Department of Immigration and Border Protection. Available from: https://www.tisnational.gov.au/

[30] Useful Emergency Medicine Resources [Internet]. Australasian College for Emergency Medicine. Available from: http://elearning.acem.org.au/course/index.php?categoryid=29

[31] 22305 – Refugee Health: GP Learning [Internet]. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Available from: http://www.racgp.org.au/education/courses/activitylist/activity/?id=17726&q=keywords%3drefugee%2bhealth

[32] Courses and Education [Internet]. The Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture Inc. Available from: http://www.foundationhouse.org.au/webinars/

[33] Caring for refugee patients in general practice: a desktop guide. 4th ed. Victorian Refugee Health Network; 2012 Mar.

[34] Translated resources: Translated health information [Internet]. Victorian Refugee Health Network. Available from: http://refugeehealthnetwork.org.au/translated-resources/

[35] National Directory of Asylum Seeker and Refugee Service Providers. Asylum Seeker Resource Centre; 2013 Aug. Available from: http://www.asrc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/National-Directory-of-Asylum-Seeker-and-Refugee-Service-Providers-August-2013.pdf

[36] Refugee Action Coalition Website [Internet]. Available from: http://www.refugeeaction.org.au/

He was just about my age, but his face was pale, his cheeks cavernous, and there was a weariness in his every movement; he was too weak to speak or even swallow well. It was as if he had been drained of all his youth.

He was just about my age, but his face was pale, his cheeks cavernous, and there was a weariness in his every movement; he was too weak to speak or even swallow well. It was as if he had been drained of all his youth.