University league tables are becoming something of an obsession. Their appeal is testament to the ‘at a glance’ approach used to convey a university’s standing, either nationally or internationally. League tables attract public attention and shape the behaviour of universities and policy makers. Their demand is a product of the increasing globalisation of higher education, tighter allocation of funding, and ultimately the recruitment of foreign students. Medical schools are not immune to this phenomenon, and are banished to a rung on a ladder year after year according to a formula that aggregates subjectively chosen indicators. While governments and other stakeholders are placing growing importance on the role of league tables, it is necessary to scrutinise the flaws in their methodology and reliability in measuring the quality of medical schools.

University league tables are becoming something of an obsession. Their appeal is testament to the ‘at a glance’ approach used to convey a university’s standing, either nationally or internationally. League tables attract public attention and shape the behaviour of universities and policy makers. Their demand is a product of the increasing globalisation of higher education, tighter allocation of funding, and ultimately the recruitment of foreign students. Medical schools are not immune to this phenomenon, and are banished to a rung on a ladder year after year according to a formula that aggregates subjectively chosen indicators. While governments and other stakeholders are placing growing importance on the role of league tables, it is necessary to scrutinise the flaws in their methodology and reliability in measuring the quality of medical schools.

Academic league tables, the brainchild of Bob Morse, were developed for the US News and World Report 30 years ago. [1] They were pioneered to meet a perceived market need for more transparent, comparative data about educational institutions. [1-3] Despite being vilified by critics, several similar ranking systems emerged in other countries in response to the introduction of, or rise in, tertiary education tuition fees. [1-3] League tables have since garnered mass appeal and now feature as a staple component of the education media cycle. They often take on the form of ‘consumer guides’ produced by commercial publishing firms who seek a return for their product. [1]

Although in existence for less than a decade, the Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings, along with the Quacquarelli (QS) World University Rankings and Shanghai Jiao Tong University Academic Ranking of World Universities are considered the behemoths of international university rankings. They provide a snapshot of the top universities overall and by discipline. From 2004 to 2009 THE, a British publication, in association with QS, published the annual THE–QS World University Rankings, however, the two companies then parted ways due to differences over methodology. The following year, QS assumed sole publication of rankings produced with the original methodology, while THE developed a novel rankings approach in partnership with Thomson Reuters. Many countries also generate national rankings by pitting their universities against each other – Australia’s answer being the Good Universities Guide.

League tables employ various methodologies to rank universities. Most involve a three stage process: first, data is collected on indicators; second, the data for each indicator is scored; and third, the scores from each indicator are weighted and aggregated. [3] The THE rankings use thirteen performance indicators, grouped into five areas including teaching, research, citations, industry income and international outlook. [4] Teaching has a 30% weighting and constitutes a reputational survey (15%), PhD awards per academic (6%), undergraduates admitted per academic (4.5%), income per academic (2.25%) and PhD/Bachelor awards (2.25%). [4,5] QS also uses a similar construct to render their final rankings. In contrast, the Shanghai rankings are established solely on research credentials such as the number of Nobel- and Fields-winning alumni/faculty and highly cited researchers, and the number of non-review articles published in Nature and Science. [6]

The influence of ranking tables has grown to such an extent that various vested interests indulge in rankings for different reasons. [1-3,7-9] A 2006 international survey revealed that 63% of higher education leaders made strategic, organisational, managerial or academic decisions based on rankings. [7] This is not always for the benefit of students or staff, and sometimes simply reflects the desire of a senior team to appear to have had an easily-identifiable impact. It is claimed that rankings have also influenced national governments, particularly in the allocation of funding, quality assessment and efforts to create ‘world class’ universities. [8] Furthermore, there is limited evidence that employers use ranking lists as part of the selection of graduate recruits. [8]

Academic league tables are no strangers to criticism, reflecting methodological, pragmatic, moral and philosophical concerns. Critics argue that ranking lists have applied the metaphor of league tables from the world of sport; a simplistic and incapable tool for evaluating the complex systems of higher education. [3] Rankings are guided by ‘what sells in the market’ rather than the rigorous quality assurance practices of academic bodies.

The world’s main ranking systems bear little resemblance to each other, owing to the fact that they use different indicators and weightings to arrive at a measure of quality. [1-3,8,9,11] According to a study by Ioannidis et al., [10] the concordance between the 2006 rankings by Shanghai and the Times is modest at best, with only 133 universities holding positions in both of the top 200 lists. The publishers of these tables impose a specific definition of quality onto the institutions being ranked, by arbitrarily establishing a set of indicators and assigning each a weight with little theoretical basis. [1-3,8] Readers are left oblivious to the fact that many other legitimate indicators could have been adopted. To the reader, the author’s judgement is, in effect, final. Many academics are of the view that rankings do not take into account the important qualities of an educational institution that cannot be measured by weightings and numbers. [8]

Statistical discrepancies also compound the tenuous nature of league tables. Often institutions are ranked even when differences in the data are not statistically significant. [1-3,8] There have been many instances where data to be used in compiling ranking scores are missing or unavailable, especially in international comparisons. [1-3,8] Moreover, data availability is a source of bias, whereby publishers opt for convenient and readily-available date, at the expense of accuracy and relevancy. [1-3,8]

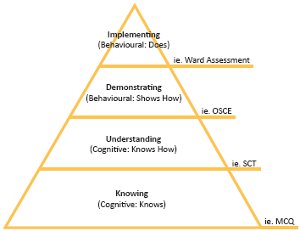

Another cause for concern is that rankings place a significant emphasis on research while minimising the role of education in universities. [5] Most educators would recognise that the indicators for quality teaching and learning are limited. [1-3,8] Various proxies for teaching ‘quality’ are used, including average student-staff ratios. [1-3,8,11] The lack of robust data relating to teaching quality is attributed to its difficult, expensive and time-consuming nature. [2] When considering that teaching quality is one of the key dimensions of medical education, its neglected importance severely compromises the meaning of any data produced by these tables.

The main mechanism for quality assurance and evaluation amongst medical schools at present is regular accreditation by national or regional accreditation bodies. [5] The Australian Medical Council (AMC) is responsible for setting out the principles and standards of Australian medical education, including assessment. The ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach of ranking tables is a futile means to effectively measure the quality of medical schools. Medical education is characterised by a range of unique indicators, for example, clinical teaching hours and global/rural health exposure. As a direct consequence of accreditation bodies, most medical schools deliver a consistent level of education and yield competent interns to practice in the Australian healthcare system. By contrast, league tables are over-simplified assessment tools for evaluating the quality of medical education, and even have the potential to harm the standards of education. [10]

Although league tables are not exalted and revered to the same degree as in the US or Europe, Australia is inadvertently heeding this imperious trend. League tables are nothing more than ‘popularity polls’, and should not become an instrument for measuring the quality of universities and medical education.

References

[1] Usher A, Savino M. A world of difference: a global survey of university league tables. Toronto (ON): Education Policy Institute; 2006 Jan. 63 p.

[2] Stella A, Woodhouse D. Ranking of higher education institutions. Melbourne: Australian Universities Quality Agency; 2006 Aug. 30 p.

[3] Marginson S. Global university rankings: where to from here. Asia Pacific Association for International Education. 2007 Mar 7-9; Singapore. Melbourne: Centre for the Study of Higher Education; 2007 Mar.

[4] Baty P. Rankings methodology. Times Higher Education; 2011 Oct 6. [updated 2012; cited 2012 Apr 7]. Available from: http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/world-university-rankings/2011-2012/analysis-rankings-methodology.html

[5] Harden RM, Wilkinson D. Excellence in teaching and learning in medical education. Med Teach. 2011;33:95-6.

[6] Liu NC, Cheng Y. The academic rankings of world universities. Higher Education in Europe. 2005 Jul;30(2);127-36.

[7] Hazelkorn E. Handle with care [Internet]. Time Higher Education; 2010 Jul 8. [updated 2010 Jul 8; cited 2012 Apr 7]. Available from: http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story. asp?storycode=412342.

[8] Lee H. Rankings of higher education institutions: a critical review. Qual High Educ. 2008 Nov;14(3):187-207.

[9] Saisana M, D’Hombres B. Higher education rankings: robustness issues and critical assessment. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2008. 106 p.

[10] Ioannidis JPA, Patsopoulos NA, Kavvoura FK, Tatsioni A, Evangelou E, Kouri I, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Liberopoulos G. International ranking systems for universities and institutions: a critical appraisal. BMC Med. 2007 Oct 25; 5(30).

[11] McGaphie WC, Thompson, JA. America’s best medical schools: a critique of the U.S. news and world report rankings. Acad Med. 2001 Oct; 76(10):985-92