In early 2013, Ban Ki-Moon, Margaret Chan and Kofi Annan had something in common: they may be completely unaware of it, but I saw them speaking in Geneva, and not merely because I lurked around Palais de Nations. Rather, wielding my very own blue United Nations (UN) ID card as an intern at the World Health Organization headquarters (WHO), I became a de facto insider to events on the international stage.

Between January and March, I undertook an 11 week internship with the WHO Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) Program in the Clinical Procedures Unit, Department Health Systems Policies and Workforce. The WHO is the directing and coordinating authority for health within the UN. It is responsible for providing leadership on global health issues, setting the research agenda, setting and articulating norms, standards and evidence-based policy options, providing technical support to countries, and monitoring and assessing health trends. [1] At some point during your studies, you will encounter material developed and disseminated by the WHO. You may have cited WHO policies in your assignments, looked up country statistics from the Global Health Observatory before your elective, or at least seen the ubiquitous Five Moments for Hand Hygiene posters, which emerged from WHO guidelines. [2] In other words, if you haven’t heard of the WHO or don’t recognize the logo, then I suggest taking a break from textbooks and click around the many fascinating corners of their website. Perhaps watch Contagion for a highly stylized (but filmed partially on location) view of an aspect of their work. [3]

The WHO and Surgery

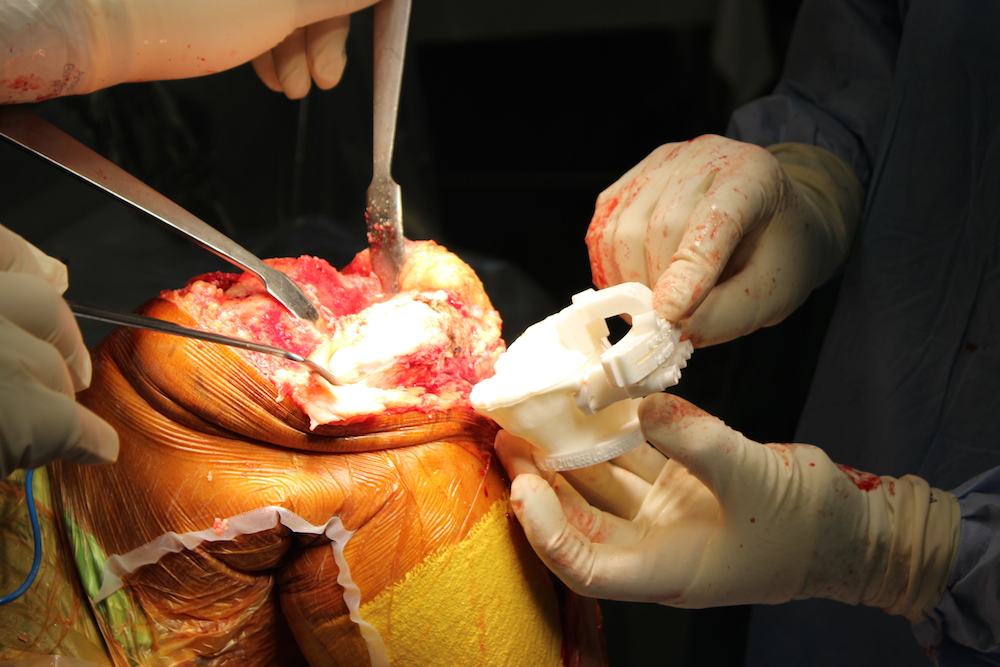

The WHO established the EESC Program in 2005, in response to growing recognition of the unaddressed burden of mortality and morbidity caused by treatable surgical conditions. [4] This reflects the lack of prioritization of surgical care systems in national health plans and the ongoing public health misconception that surgical care is not cost-effective and impacts only upon a minority of the population. [5] These misconceptions apply as much to those in the field of public health, as well as to surgeons on the ground and in the literature, let alone those at other agencies. This was reflected by the question I all too commonly faced when explaining my internship: “The WHO is involved in surgery?”

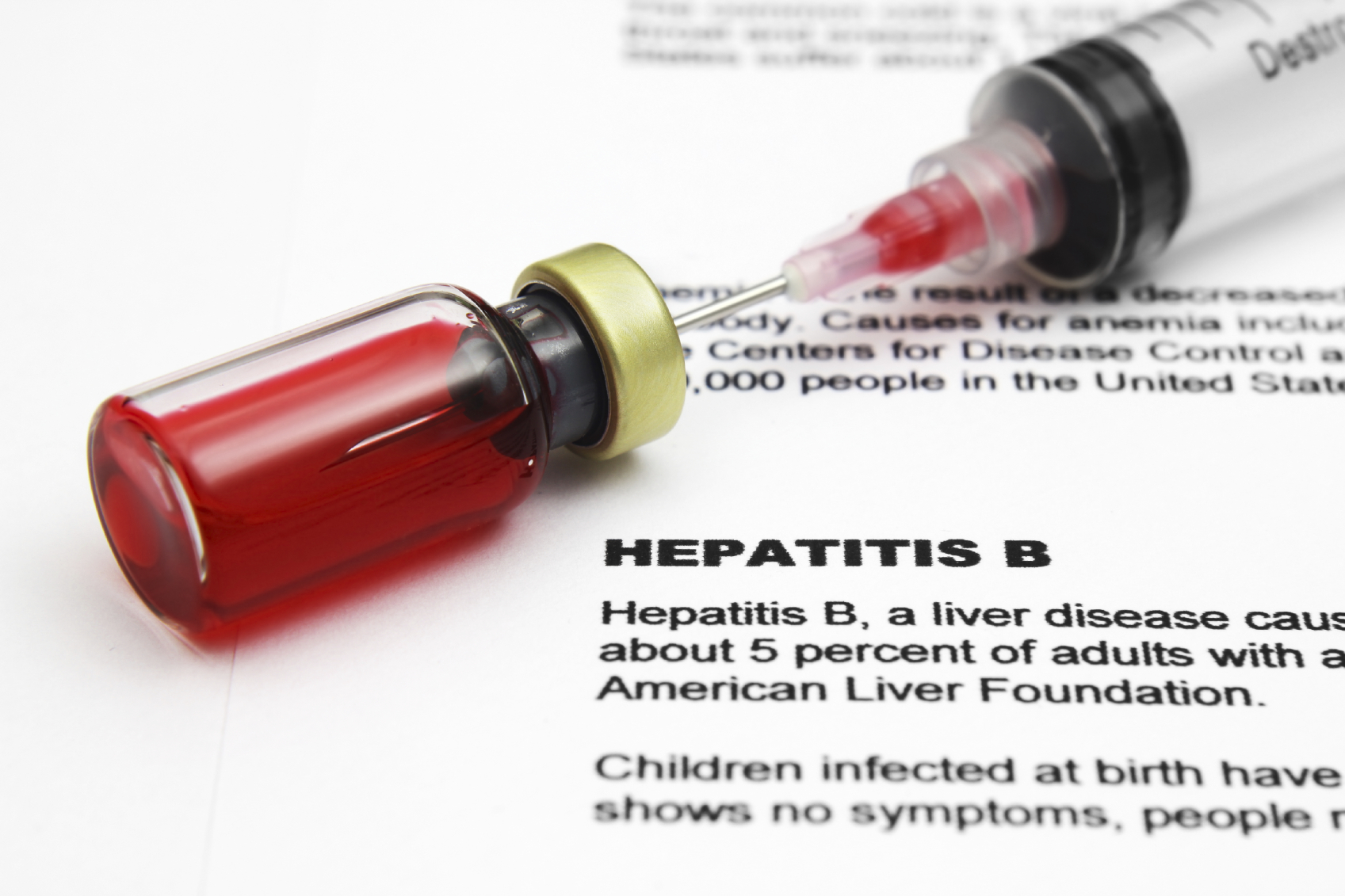

In reality, surgical conditions contribute to an estimated 11% of the global burden of disease. It is a field that cuts across a number of public health priorities. [6] For example, progress on many of the Millennium Development Goals demands the prioritization of surgical care systems, most obviously in connection with maternal and newborn care. [7] Timely access to surgical interventions, including resuscitation, pain management and caesarean section, are vital to reducing maternal mortality. [8] Even in its most basic forms, surgical procedures can play a role in both preventative and curative therapies, from male circumcision in relation to HIV control to the aseptic suturing of wounds. However, surgery also has a very real impact on poverty by addressing the underlying causes of disability which often contribute to unemployment and debt. These include the management of congenital and injury incurred disabilities and preventable blindness. [9] Surgery can be a complex intervention because it relies upon numerous elements of the health system to be functioning completely. There is little point in having access to basic infrastructural amenities like electricity, running water and oxygen, when at the moment of an emergency it is unavailable. Similarly, having equipment and supplies alone are insufficient when there is a shortage of a skilled workforce to wield them.

The WHO EESC is dedicated to supporting life-saving surgical care systems in the areas of greatest need, through collaborations between the WHO, Ministries of Health and other agencies. The WHO Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (GIEESC) is an online network linking academics, policy makers, health care providers and advocates across 100 countries. Together, they developed the WHO Integrated Management for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (IMEESC) toolkit to equip health and government workforces with WHO recommendations, skills and resources, focusing on emergency, trauma, obstetrics and anaesthesia, in order to improve the quality of, and access to, surgical services. [4]

In terms of my role, let me begin with the caveat that, as an intern, one can be called upon to conduct a wide variety of tasks within the huge scope of the WHO. My experiences differed greatly from those of colleagues and are not necessarily reflective of what one may encounter in other departments, or even in the same program at different times of year. I applied through the online internship application, but amongst my colleagues, this was in fact a rarity. [10] By far the majority of interns had applied directly or through their university to the specific areas of the WHO that aligned with their interests.

I undertook both administrative and research tasks, working very closely with my supervisor, Dr. Meena Cherian. There is a paucity of evidence capturing the surgical capacity, including infrastructure, equipment, health workforce and surgical procedures provided, across facilities in low- and middle-income countries. Through the GIEESC network, the WHO Situation Analysis Tool captures the capacity of first-referral health facilities to provide emergency and essential surgical care. [4] One of my key roles was in data collation and analysis. In terms of tangible outcomes, in the span of my internship I was able to contribute to two research papers for submission. In terms of my education, however, it was the administrative roles that demonstrated many of the key lessons about working in international organizations, and for which I am most grateful. Although menial tasks like photocopying and editing PowerPoint presentations can seem futile, carrying those documents into meetings allows one to witness the behind-the-scenes exchanges that drive many international organizations. This deepened my understanding of the WHO’s functions, strengths and limitations. In my experience, exacerbated by funding limitations and the rise of game-changing new players from the non-government sector, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, attracting and justifying resource allocation to marginalized areas like surgery becomes a full-time job in itself. Opportunities for collaboration with such NGOs can result in successful innovation and programming, as with the polio eradication campaign. However, although inter-sector and inter-department collaboration is seemingly an obvious win-win, the undercurrents of turf wars and politicization of health issues can make such collaborations seem like a delicate diplomatic performance. Effective WHO engagement with external stakeholders cannot come at the cost of its intergovernmental nature or independence from those with vested interests. [1] Such are the limitations imposed on international organizations by the international community and the complex relationships between member states.

Ultimately, learning to collaborate with colleagues across cultural, economic, resource and contextual barriers under the tutelage of my supervisor has implications for any future endeavor in our increasingly globalized workplaces. Learning to navigate such competing social and political interests is as applicable to clinical practice as it is to public health. Furthermore, the Experts for Interns program initiated by the WHO Intern Board provides bi-weekly lunchtime seminars specifically designed to broaden the scope of the intern experience by facilitating discussion with experts in various fields. [11] These were particularly valuable as an opportunity to ask direct questions, challenge preconceived notions and reexamine the historical development of public health, global health and the role and scope of the WHO.

Personal Highlights and Challenges

Geneva is an international city, home not only to WHO HQ and the United Nations in Europe, but also to a number of other UN Agencies and international non-governmental organisations, including Médecins Sans Frontières and the International Committee of the Red Cross. This means that, at any given time, there are a huge number of international and cultural events occurring. During my stay alone, there was the WHO Executive Board Meeting, the Geneva Human Rights Film Festival, a number of conferences, the UN Human Rights Council and some truly high profile speakers. Hans Rosling, the rock star of epidemiology and a founder of GapMinder, has put together a great TED Talk, but seeing him speak in person was one of my most lively, educative and stimulating experiences. [12,13] It is a memory I will treasure and return to for motivation, particularly when rote learning another fact for an exam seems impossible. For many of us who aspire towards a career in global health, seeing these famous faces and learning firsthand about their work and career pathways is more than just inspiring, it can become a raison d’être.

From a slightly more cavalier perspective, Switzerland is centrally located in Europe, and Geneva as an international city is a great base from which to travel. It is easy to find sale flights to major European destinations, and the train to Paris takes only three hours. As an unpaid intern, your weekends are your own and most supervisors are generous about allowing travel grace. The opportunity to explore a new city every weekend is alluring, and with options like the demi-tariff, the half-priced fares on Swiss trains, it’s certainly a possibility. The Geneva and Lac Leman region features charming villages and cities with the sort of breathtaking mountain views that makes everything look like a postcard, not least if it’s covered in a blanket of pristine white snow. This is the other key attraction of Geneva in winter: if you’re into snow sports, you will be based within an easy day trip to some of the best pistes in the world. Indeed, the Swiss penchant for such trips seems to be why Sundays find Geneva a ghost town of sorts. Aside from the odd museum, absolutely nothing is open on Sundays, to the point where if you make my mistake of arriving on Sunday, it may be difficult to even find food.

Even if you can find food on a Sunday, affording it and anything else in Geneva is not easy. The cost of living is high, and, despite the high turnover of ex-pat staff, finding a place to stay is extremely difficult. As Australians we have it luckier than most, by being able to make use of OS-HELP loans while studying overseas. There is an ongoing discussion about paid internships within the UN, and there are varying practices amongst agencies. Some, notably the International Labor Organization, pay interns, while the WHO and others do not. This has become an advocacy issue amongst interns, as it severely limits access to the educative and career-oriented experiences internships provide for those from middle- and low-income nations. However, it seems unlikely that this will change in the near future. Nonetheless, with careful saving, planning and some basic austerity measures, finances should not deter you from this experience.

Another potential challenge is that Geneva is in francophone Switzerland; it is geographically surrounded on most sides by France. Many WHO staff and interns live, or at least shop, across the French border, where I discovered amazing supermarkets with entire aisles devoted to Swiss and French cheeses and chocolate. As a hopeless Francophile, this was a delicious highlight. I took classes and developed my French while safely working in a predominantly anglophone environment. If you have never studied French, then learning basics pre-arrival would be recommended, though it is possible to get around Geneva without, as the locals are very generous in this regard. However, there were often times when my linguistic limitations perpetuated anglophone dominance, forcing colleagues to transition into my language of choice. Such language barriers can also contribute to cultural misunderstandings. For example, early on I committed the fauxpas of being too casual in the more hierarchical workplace, where professional titles were used even in personal conversations. Coming from the more egalitarian Australian context, this can come as something of a culture shock, though it varies considerably between different offices and departments.

As a result of my experiences, I am now both more cynical and more hopeful about the future of global health. The bureaucratic limitations of the WHO are also where its authority lies. Sifting through convoluted Executive Board meetings, it is easy to become skeptical about the relevance of this 65-year old organization. However, this belies the power of health mandates supported by member state consensus, whether in regards to the Tobacco Free Initiative or the Millennium Development Goals. Such change and reform, though slow, is broad reaching and invigorating.

Finally, the most significant and meaningful experiences I shared during my internship were not with the famous faces of global health, but with my peers. Across the various organizations based in Geneva, there are a huge number of interns from all over the world. Making connections with these kindred spirits, who shared my interests and a similar desire for an international career, was such a privilege. Even when our areas of interest did not intersect, it was amazing to learn from the expertise of fellow interns and students. For example, a fascinating experience was encountering a student at CERN (Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire, better known to us non-physicists as the home of the Large Hadron Collider) with whom I was able to have a sticky beak at the labs and lifestyles of modern physics’ greatest thinkers. Just as he is progressing towards becoming a don of theoretical physics, at some point in the next few decades many of the friends I’ve made through this internship are going to become the next generation of global health leaders. More importantly, creating such networks across continents and across specializations has been instrumental in shaping my sense of self and perspective, and has left an indelible mark in the form of new education, career and lifestyle aspirations.

Where to from here for you

There is an online intern application through the WHO website. Although I completed this as my elective term, I also encountered a number of students from Australia for whom this was a summer opportunity to experience the organization, or as part of their research. I would strongly urge any student with interests in public health, global health, policy or research to consider applying for this opportunity, and to do so by contacting the departments of your interests directly.

In terms of surgery and global health, please visit the EESC program website at www.who.int/surgery for further information, and to become a GIEESC member.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge the generosity of the WHO Clinical Procedures Unit, particularly Dr. Meena Cherian of the WHO Emergency and Essential Surgical Care Program, who hosted her internship, and the financial support of the Australian government OS-HELP loan program.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Correspondence

L Hashimoto-Govindasamy: laksmisg@gmail.com

References

[1] World Health Organization. About the WHO. [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 March 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/about/en/

[2] World Health Organization. Clean care is safer care: five moments in hand hygiene. [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 March 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/tools/Five_moments/en/

[3] International Movie Database. Contagion. [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 March 26]. Available from: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1598778/

[4] World Health Organization. Emergency and essential surgical care. [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 March 26]/ Available from: http://www.who.int/surgery/en/

[5] Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, Haynes AB, Lipsitz SR, Berry WR, Gawande AA. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modeling strategy based on available data. Lancet. 2008;372:139–44.

[6] Debas HT, Gosselin R, McCord C, Thind A. Surgery. In: Jamison D, editor. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd ed. New York. Oxford University Press; 2006.

[7] United Nations. Millennium Development Goals. [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 March 26]. Available from: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/

[8] Kushner A, Cherian M, Noel L, Spiegel DA, Groth S, Etienne C. Addressing the Millennium Development Goals from a surgical perspective: essential surgery and anesthesia in 8 low- and middle-income countries. Arch Surg. 2010;145(2):154-160.

[9] PLOS Medicine Editors. A crucial role for surgery in reaching the UN Millennium Development Goals. PLOS Med. 2008;5(8):e182.doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050182

[10] World Health Organization. WHO employment: WHO internships. [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 March 26]. Available from: http://www.who.int/employment/internship/interns/en/index1.html

[11] WHO Interns. Experts for interns (E-4-I). [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 March 26]. Available from: http://whointerns.weebly.com/experts-for-interns.html

[12] TED: Ideas worth spreading. Hans Rosling: Stats that reshape your worldview. [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2013 March 26]. Available from: http://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_shows_the_best_stats_you_ve_ever_seen.html

[13] Gapminder. Gapminder: for a fact-based worldview. [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2013 March 26]. Available from: http://www.gapminder.org/