Introduction

An arterial aneurysm is defined as a localised dilation of an artery to greater than 50% of its normal diameter. [1] Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is common with an incidence five times greater in men than women. [2] In Australia the prevalence of AAAs is 4.8% in men aged 65-69 years rising to 10.8% in those aged 80 years and over. [3] The mortality from ruptured AAA is very high, approximately 80%, [4] whilst the aneurysm-related mortality of surgically treated, asymptomatic AAA is around five percent. [5] In Australia AAAs make up 2.4% of the burden of cardiovascular disease, contributing 14,375 disability adjusted life years (DALYs), ahead of hypertension (14,324) and valvular heart disease (13,995). [6] Risk factors for AAA of greater than four centimetres include smoking (RR=3-5), family history (OR=1.94), coronary artery disease (OR= 1.52), hypercholesterolaemia (OR= 1.44) and cerebrovascular disease (OR= 1.28). [7] Currently, the approach to AAA management involves active surveillance, risk factor reduction and surgical intervention. [8]

The surgical management of AAAs dates back over 3000 years and has evolved greatly since its conception. Over the course of surgical history arose three landmark developments in aortic surgery: crude ligation, open repair and endovascular AAA repair (EVAR). This paper aims to examine the development of surgical interventions for AAA, from its experimental beginnings in ancient Egypt to current evidence based practice defining EVAR therapy, and to pay homage to the surgical and anatomical masters who made significant advances in this field.

Early definition

The word aneurysm is derived from the Greek aneurysma, for ‘widening’. The first written evidence of AAA is recorded in the ‘Book of Hearts’ from the Eber Scolls of ancient Egypt, dating back to 1550 BC. [9] It stated that “only magic can cure tumours of the arteries.” India’s Sushruta (800 ~ 600 BC) mentions aneurysm, or ‘Granthi’, in chapter 17 of his great medical text ‘Sushruta Samhita’. [10] Although undistinguished from painful varicose veins in his text, Sushruta shared a similar sentiment to the Egyptians when he wrote “[Granthi] can be cured only with the greatest difficulty”. Galen (126-c216 AD), a surgeon of ancient Rome, first formally described these ‘tumours’ as localised pulsatile swellings that disappear with pressure. [11] He was also first to draw anatomical diagrams of the heart and great vessels. His work with wounded gladiators and that of the Greek surgeon Antyllus in the same period helped to define traumatic false aneurysms as morphologically rounded, distinct from true, cylindrical aneurysms caused by degenerative dilatation. [12] This work formed the basis of the modern definition.

Early ligation

Antyllus is also credited with performing the first recorded surgical interventions for the treatment of AAA. His method involved midline laparotomy, proximal and distal ligation of the aorta, central incision of the aneurysm sac and evacuation of thrombotic material. [13] Remarkably, a few patients treated without aseptic technique or anaesthetic managed to survive for some period. Antyllus’ method was further described in the seventh century by Aetius, whose detailed paper ‘On the Dilation of Blood Vessels,’ described the development and repair of AAA. [14] His approach involved stuffing the evacuated sac with incense and spices to promote pus formation in the belief that this would aid wound healing. Although this belief would wane as knowledge of the process of wound healing improved, Antyllus’s method would remain largely unchanged until the late nineteenth century.

Anatomy

The Renaissance saw the birth of modern anatomy, and with it a proper understanding of aortic morphology. In 1554 Vesalius (1514-1564) produced the first true anatomical plates based on cadaveric dissection, in ‘De Humani Corporis Fabrica.’ [15] A year later he provided the first accurate diagnosis and illustrations of AAA pathology. In total, Vesalius corrected over 200 of Galen’s anatomical mistakes and is regarded as the father of modern anatomy. [16] His discoveries began almost 300 years of medical progress characterised by the ‘surgeon-anatomist’, paving the way for the anatomical greats of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was during this period that the great developments in the anatomical and pathological understanding of aneurysms took place.

Pathogenesis

Ambroise Pare (1510-1590) noted that aneurysms seemed to manifest following syphilis, however he attributed the arterial disease to syphilis treatment rather than the illness itself. [17] Stress on the arteries from hard work, shouting, trumpet playing and childbirth were considered other possible causes. Morgagni (1682-1771) described in detail the luetic pathology of ruptured sacular aortic aneurysms in syphilitic prostitutes, [18] whilst Monro (1697-1767) described the intima, media and adventitia of arterial walls. [19] These key advances in arterial pathology paved the way for the Hunter Brothers of London (William Hunter [1718-1783] and John Hunter [1728-1793]) to develop the modern definitions of true, false and mixed aneurysms. Aneurysms were now accepted to be caused by ‘a disproportion between the force of the blood and the strength of the artery’, with syphilis as a risk factor rather than a sole aetiology. [12] As life expectancy rose dramatically in the twentieth century, it became clear that syphilis was not the only cause of arterial aneurysms, as the great vascular surgeon Rudolf Matas (1860-1957) stated: “The sins, vices, luxuries and worries of civilisation clog the arteries with the rust of premature senility, known as arteriosclerosis or atheroma, which is the chief factor in the production of aneurysm.” [20]

Modern ligation

The modern period of AAA surgery began in 1817 when Cooper first ligated the aortic bifurcation for a ruptured left external iliac aneurysm in a 38 year old man. The patient died four hours later; however, this did not discourage others from attempting similar procedures. [21]

Ten further unsuccessful cases were recorded prior to the turn of the twentieth century. It was not until a century later, in 1923, that Matas performed the first successful complete ligation of the aorta for aneurysm, with the patient surviving seventeen months and dying from tuberculosis. [22] Described by Osler as the ‘modern father of vascular surgery’, Matas also developed the technique of endoaneurysmorrhaphy, which involved ligating the aneurysmal sac upon itself to restore normal luminal flow. This was the first recorded technique aiming to spare blood flow to the lower limbs, an early prelude to the homograft, synthetic graft and EVAR.

Early Alternatives to Ligation

Despite Matas’ landmark success, the majority of surgeons of the era shared Suchruta’s millennia-old fear of aortic surgery. The American Surgical Association wrote in 1940, “the results obtained by surgical intervention have been discouraging.” Such fear prompted a resurgence of techniques introducing foreign material into the aneurismal lumen with the hope of promoting thrombosis. First attempted by Velpeau [23] with sewing needles in 1831, this technique was modified by Moore [24] in 1965 using 26 yards of iron wire. Failure of aneurysm thrombosis was blamed on ‘under packing’ the aneurysm. Corradi used a similar technique, passing electric current through the wire to introduce thrombosis. This technique became known as fili-galvanopuncture or the ‘Moore-Corradi method’. Although this technique lost popularity for aortic procedures, it marked the beginning of electrothrombosis and coiling of intracranial aneurysms in the latter half of the twentieth century. [25]

Another alternative was wrapping the aneurysm with material in an attempt to induce fibrosis and contain the aneurysm sac. AAA wrapping with cellophane was investigated by Pearse in 1940 [26] and Harrison in 1943. [27] Most notably, Nissen, the pioneer of Nissen fundoplication for hiatus hernia, famously wrapped Albert Einstein’s AAA with cellophane in 1948. [28] The aneurysm finally ruptured in 1955, with Einstein refusing surgery: “I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially.” [28]

Anastomosis

Many would argue that the true father of modern vascular techniques is Alexis Carrel. He conducted the first saphenous vein bypass in 1948, the first successful kidney transplant in 1955 and the first human limb re-implantation in 1962. [13,29] Friedman states that “there are few innovations in cardiac and vascular surgery today that do not have roots in his work.” [13] Perhaps of greatest note was Carrel’s development of the triangulation technique for vessel anastomosis.

This technique was utilised by Crafoord in Sweden in 1944, in the first correction of aortic coarctation, and by Shumacker [30] in 1947 to correct a four centimetre thoracic aortic aneurysm secondary to coarctation. Prior to this time, coarctation was treated in a similar fashion to AAA, with ligation proximal and distal to the defect. [31] These developments would prove to be great milestones in AAA surgery as the first successful aortic aneurysm resection with restoration of arterial continuity.

Biological grafts

Despite this success, restoration of arterial continuity was limited to the thoracic aorta. Abdominal aneurysms remained too large to be anastomosed directly and a different technique was needed. Carrel played a key role in the development of arterial grafting, used when end-to-end anastomosis was unfeasible. The original work was performed by Carrel and Guthrie (1880-1963) with experiments transplanting human and canine vessels. [32,33] Their 1907 paper ‘Heterotransplantation of blood vessels’ [34] began with:

“It has been shown that segments of blood vessels removed from animals may be caused to regain and indefinitely retain their function.”

This discovery led to the first replacement of a thrombosed aortic bifurcation by Jacques Oudot (1913-1953) with an arterial homograft in 1950. The patient recovered well, and Oudot went on to perform four similar procedures. The landmark first AAA resection with restoration of arterial continuity can be credited to Charles Dubost (1914-1991) in 1951. [35] His patient, a 51 year old man, received the aorta of a young girl harvested three weeks previously. This brief period of excitement quickly subsided when it was realised that the long-term patency of aortic homografts was poor. It did, however, lay the foundations for the age of synthetic aortic grafts.

Synthetic grafts

Arthur Voorhees (1921-1992) can be credited with the invention of synthetic arterial prosthetics. In 1948, during experimental mitral valve replacement in dogs, Voorhees noticed that a misplaced suture had later become enveloped in endocardium. He postulated that, “a cloth tube, acting as a lattice work of threads, might indeed serve as an arterial prosthesis.” [36] Voorhees went on to test a wide variety of materials as possible candidates from synthetic tube grafts, resulting in the use of vinyon-N, the material used in parachutes. [37] His work with animal models would lead to a list of essential structural properties of arterial prostheses. [38]

Vinyon-N proved robust, and was introduced by Voorhees, Jaretski and Blakemore. In 1952 Voorhees inserted the first synthetic graft into a ruptured AAA. Although the vinyon-N graft was successfully implanted, the patient died shortly afterwards from a myocardial infarction. [39] By 1954, Voorhees had successfully implanted 17 AAAs with similar grafts. Schumacker and Muhm would simultaneously conduct similar procedures with nylon grafts. [40] Vinyon-N and nylon were quickly supplanted by Orlon. Similar materials with improved tensile strength are used in open AAA repair today, including Teflon, Dacron and expanded Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). [41]

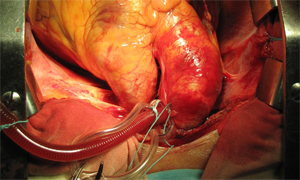

Modern open surgery

With the development of suitable graft material began the golden age of open AAA repair. The focus would now be largely on the Americans, particularly with surgeons DeBakey (1908-2008) and Cooley (1920) leading the way in Houston, Texas. In the early 1950s, DeBakey and Cooley developed and refined an astounding number of aortic surgical techniques. Debakey would also classify aortic dissection into different types depending on their site. In 1952, a year after Dubost’s first success in France, the pair would perform the first repair of thoracic aneurysm, [42] and a year later, the first aortic arch aneurysm repair. [43] It was around this time that the risks of spinal cord ischaemia during aortic surgery became apparent. Moderate hypothermia was first used and then enhanced in 1957, with Gerbode’s development of extracorporeal circulation, coined ‘left heart bypass’. In 1963, Gott expanded on this idea with a heparin-treated polyvinyl shunt from ascending to descending aorta. By 1970, centrifuge-powered, left-heart bypass with selective visceral perfusion had been developed. [44] In 1973, Crawford simplified DeBakey and Cooley’s technique by introducing sequential clamping of the aorta. By moving clamps distally, Crawford allowed for reperfusion of segments following the anastomoses of what had now become increasingly more complex grafts. [45] The work of DeBakey, Cooley and Crawford paved the way for the remarkable outcomes available to modern patients undergoing open AAA repair. Where once feared by surgeons and patients alike, in-hospital mortality following elective, open AAA now has a 30-day all-cause mortality of around five percent. [58]

Imaging

It must not be overlooked that significant advances in medical imaging have played a major role in reducing the incidence of ruptured AAAs and the morbidity and mortality associated with AAAs in general. The development of diagnostic ultrasound began in the late 1940s and 50s, with simultaneous research by John Wild in the United States, Inge Elder and Carl Hertz in Sweden and Ian Donald in Scotland. [46] It was the latter who published ‘Investigation of Abdominal Masses by Pulsed Ultrasound,’ regarded as one of the most important papers in diagnostic imaging. [47] By the 1960s, Doppler ultrasound would provide clinicians with both a structural and functional view of vessels, with colour flow Doppler in the 1980s allowing images to represent the direction of blood flow. The Multicentre Aneurysm Study showed that ultrasound screening resulted in a 42% reduction in mortality from ruptured AAAs over four years to 2002. [48] Ultrasound screening has resulted in an overall increase in hospital admissions for asymptomatic aneurysms; however, increases in recent years cannot be attributed to improved diagnosis alone, as it is known that the true incidence of AAA is also increasing in concordance with Western vascular pathology trends. [49]

In addition to the investigative power of ultrasound imaging, computed tomography (CT) scanners became available in the early 1970s. As faster, higher-resolution spiral CT scanners became more accessible in the 1980s, the diagnosis and management of AAAs became significantly more refined. [50] CT angiography has emerged as the gold standard for defining aneurysm morphology and planning surgical intervention. It is crucial in determining when emergent treatment is necessary, when calcification and soft tissue may be unstable, when the aortic wall is thickened or adhered to surrounding structures, and when rupture is imminent. [51] Overall operative mortality from ruptured AAA fell by 3.5% per decade from 1954-1997. [52] This was due to both a significant leap forward in surgical techniques in combination with drastically improved imaging modalities.

EVAR

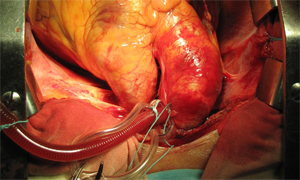

The advent of successful open surgical repair of AAAs using synthetic grafts in the 1950s proved to be the first definitive treatment for AAA. However, the procedure remained highly invasive and many patients were excluded due to medical and anatomical contraindications. [53] Juan Parodi’s work with Julio Palmaz and Héctor Barone in the late 1980s aimed to rectify this issue. Parodi developed the first catheter-based arterial approach to AAA intervention. The first successful EVAR operation was completed by Parodi in Argentina on seventh September 1990. [54] The aneurysm was approached intravascularly via a femoral cutdown. Restoration of normal luminal blood flow was achieved with the deployment of a Dacron graft mounted on a Palmaz stent. [55] There was no need for aortic cross-clamping or major abdominal surgery. Similar non-invasive strategies were explored independently and concurrently by Volodos, [56] Lazarus [57] and Balko. [58]

During this early period of development there was significant Australian involvement. The work of Michael Lawrence-Brown and David Hartley at the Royal Perth Hospital led to the manufacture of the Zenith endovascular graft in 1993, a key milestone in the development of modern-day endovascular aortic stent-grafts. [59] The first bifurcated graft was successfully implanted one year later. [60] Prof James May and his team at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney conducted further key research, investigating the causes of aortic stent failure and complications. [61] This group went on to pioneer the modular design of present day aortic prostheses. [62]

The FDA approved the first two AAA stent grafts for widespread use in 1999. Since then, technical improvements in device design have resulted in improved surgical outcomes and increased ability to treat patients with difficult aneurysmal morphology. Slimmer device profiles have allowed easier device insertion through tortuous iliac vessels. [63] Furthermore, fenestrated and branched grafts have made possible the stent-grafting of juxtarenal AAA, where suboptimal proximal neck anatomy once meant traditional stenting would lead to renal failure and mesenteric ischaemia. [64]

AAA intervention now and beyond

Today, surgical intervention is generally reserved for AAAs greater than 5.5cm diameter and may be achieved by either open or endoluminal access. The UK small aneurysm trial determined that there is no survival benefit to elective open repair of aneurysms of less than 5.5cm. [8] The EVAR-1 trial (2005) found EVAR to reduce aneurysm related mortality by three percent at four years when compared to open repair; however, EVAR remains significantly more expensive and requires more re-interventions. Furthermore, it offers no advantage with respect to all cause mortality or health related quality of life. [5] These findings raised significant debate over the role of EVAR in patients fit for open repair. This controversy was furthered by the findings of the EVAR-2 trial (2005), which saw risk factor modification (fitness and lifestyle) as a better alternative to EVAR in patients unfit for open repair. [65] Many would argue that these figures are obsolete, with Criado stating, “it would not be unreasonable to postulate that endovascular experts today can achieve far better results than those produced by the EVAR-1 trial.” [53] It is undisputed that EVAR has dramatically changed the landscape of surgical intervention for AAA. By 2005, EVAR accounted for 56% of all non-ruptured AAA repairs but only 27% of operative mortality. Since 1993, deaths related to AAA have decreased dramatically, by 42%. [53] EVAR’s shortcomings of high long-term rates of complications and re-interventions, as well as questions of device performance beyond ten years, appear balanced by the procedure’s improved operative mortality and minimally invasive approach. [54]

Conclusion

The journey towards truly effective surgical intervention for AAA has been a long and experimental one. Once regarded as one of the most deadly pathologies, with little chance of a favourable surgical outcome, AAAs can now be successfully treated with minimally invasive procedures. Sushruta’s millennia-old fear of abdominal aortic surgery appears well and truly overcome.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Correspondence

A Wilton: awil2853@uni.sydney.edu.au

References

[1] Kumar V et al. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease 8th ed. Elsevier. 2010.

[2] Semmens J, Norman PE, Lawrence-Brown MMD, Holman CDJ. Influence of gender on outcome from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. British Journal of Surgery. 2000;87:191-4.

[3] Jamrozik K, Norman PE, Spencer CA. et al. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms: lessons from a population-based study. Med. J. Aust. 2000;173:345-50.

[4]Semmens J, Lawrence-Brown MMD, Norman PE, Codde JP, Holman, CDJ. The Quality of Surgical Care Project: Benchmark standards of open resection for abdominal aortic aneurysm in Western Australia. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68:404-10.

[5] The EVAR trial participants. EVAR-1 (EndoVascular Aneurysm Repair): EVAR vs open repair in patients with abdomial aortic aneurym. Lancet. 2005;365:2179-86.

[6] National Heart Foundation of Australia. The Shifting Burden of Cardiovascular Disease. 2005.

[7] Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best-evidence systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):203-11.

[8] United Kingdom Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. UK Small Aneurysm Trial. N Eng J Med. 2002;346:1445-52.

[9] Ghalioungui P. Magic and Medical Science in Ancient Egypt. Hodder and Stoughton Ltd. 1963.

[10] Bhishagratna KKL. An English Translation of The Sushruta Samhita. Calcutta: Self Published; 1916.

[11] Lytton DG, Resuhr LM. Galen on Abnormal Swellings. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 1978;33(4):531-49.

[12] Suy R. The Varying Morphology and Aetiology of the Arterial Aneurysm. A Historical Review. Acta Chir Belg. 2006;106:354-60.

[13] Friedman SG. A History of Vascular Surgery. New York: Futura Publishing Company 1989;74-89.

[14] Stehbens WE. History of Aneurysms. Med Hist 1958;2(4):274–80.

[15] Van Hee R. Andreas Vesalius and Surgery. Verh K Acad Geneeskd Belg. 1993;55(6):515-32.

[16] Kulkarni NV. Clinical Anatomy: A problem solving approach. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. 2012;4.

[17] Paré A. Les OEuvres d’Ambroise Paré. Paris: Gabriel Buon; 1585.

[18] Morgagni GB. Librum quo agitur de morbis thoracis. Italy: Lovanni; 1767 p270-1.

[19] Monro DP. Remarks on the coats of arteries, their diseases, and particularly on the formation of aneurysm. Medical essays and Observations. Edinburgh, 1733.

[20] Matas R. Surgery of the Vascular System. AMA Arch Surg. 1956;72(1):1-19.

[21] Brock RC. The life and work of Sir Astley Cooper. Ann R Coll Surg Engl.1969; 44:1.

[22] Matas R. Aneurysm of the abdominal aorta at its bifurcation into the common iliac arteries. A pictorial supplement illustration the history of Corrinne D, previously reported as the first recored instance of cure of an aneurysm of the abdominal aorta by ligation. Ann Surg. 1940;122:909.

[23] Velpeau AA. Memoire sur la figure de l’acupuncture des arteres dans le traitement des anevrismes. Gaz Med. 1831;2:1.

[24] Moore CH, Murchison C. On a method of procuring the consolidation of fibrin in certain incurable aneurysms. With the report of a case in which an aneurysm of the ascending aorta was treated by the insertion of wire. Med Chir Trans. 1864;47:129.

[25] Siddique K, Alvernia J, Frazer K, Lanzino G, Treatment of aneurysms with wires and electricity: a historical overview. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:1102–7.

[26] Pearse HE. Experimental studies on the gradual occlusion of large arteries. Ann Surg. 1940;112:923.

[27] Harrison PW, Chandy J. A subclavian aneurysm cured by cellophane fibrosis. Ann Surg. 1943;118:478.

[28] Cohen JR, Graver LM. The ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm of Albert Einstein. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:455-8.

[29] Edwards WS, Edwards PD. Alexis Carrel: Visionary surgeon. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, Ltd 1974;64–83.

[30] Shumacker HB Jr. Coarctation and aneurysm of the aorta. Report of a case treated by excision and end-to-end suture of aorta. Ann Surg. 1948;127:655.

[31] Alexander J, Byron FX. Aortectomy for thoracic aneurysm. JAMA 1944;126:1139.

[32] Carrel A. Ultimate results of aortic transplantation, J Exp Med. 1912;15:389–92.

[33] Carrel A. Heterotransplantation of blood vessels preserved in cold storage, J Exp Med. 1907;9:226–8.

[34] Guthrie CC. Heterotransplantation of blood vessels, Am J Physiol 1907;19:482–7.

[35] Dubost C. First successful resection of an aneurysm of an abdominal aorta with restoration of the continuity by human arterial graft. World J Surg. 1982;6:256.

[36] Voorhees AB. The origin of the permeable arterial prosthesis: a personal reminiscence. Surg Rounds. 1988;2:79-84.

[37] Voorhees AB. The development of arterial prostheses: a personal view. Arch Surg. 1985;120:289-95.

[38] Voorhees AB. How it all began. In: Sawyer PN, Kaplitt MJ, eds. Vascular Grafts. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts 1978;3-4.

[39] Blakemore AH, Voorhees AB Jr. The use of tubes constructed from vinyon “N” cloth in bridging arterial defects – experimental and clinical. Ann Surg. 1954;140:324.

[40] Schumacker HB, Muhm HY. Arterial suture techniques and grafts: past, present, and future. Surgery. 1969;66:419-33.

[41] Lidman H, Faibisoff B, Daniel RK. Expanded Polytetrafluoroethene as a microvascular stent graft: An experimental study. Journal of Microsurgery. 1980;1:447-56.

[42] Cooley DA, DeBakey ME. Surgical considerations of intrathoracic aneurysms of the aorta and great vessels. Ann Surg. 1952;135:660–80.

[43] DeBakey ME. Successful resection of aneurysm of distal aortic arch and replacement by graft. J Am Med Assoc. 1954;155:1398–403.

[44] Argenteri A. The recent history of aortic surgery from 1950 to the present. In: Chiesa R, Melissano G, Coselli JS et al. Aortic surgery and anaesthesia “How to do it” 3rd Ed. Milan: Editrice San Raffaele 2008;200-25.

[45] Green Sy, LeMaire SA, Coselli JS. History of aortic surgery in Houston. In: Chiesa R, Melissano G, Coselli JS et al. Aortic surgery and anaesthesia “How to do it” 3rd Ed. Milan: Editrice San Raffaele. 2008;39-73.

[46] Edler I, Hertz CH. The use of ultrasonic reflectoscope for the continuous recording

of the movements of heart walls. Clin Physiol Funct I. 2004;24:118–36.

[47] Ian D. The investigation of abdominal masses by pulsd ultrasound. The Lancet June 1958;271(7032):1188-95.

[48] Thompson SG, Ashton HA, Gao L, Scott RAP. Screening men for abdominal aortic aneurysm: 10 year mortality and cost effectiveness results from the randomised Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study. BMJ. 2009;338:2307.

[49] Filipovic M, Goldacre MJ, Robert SE, Yeates D, Duncan ME, Cook-Mozaffari P. Trends in mortality and hospital admission rates for abdominal aortic aneurysm in England and Wales. 1979-1999. BJS 2005;92(8):968-75.

[50] Kevles BH. Naked to the Bone: Medical Imagine in the Twentieth Century. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press 1997;242-3.

[51] Ascher E, Veith FJ, Gloviczki P, Kent KC, Lawrence PF, Calligaro KD et al. Haimovici’s vascular surgery. 6th ed. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2012;86-92.

[52] Bown MJ, Sutton AJ, Bell PRF, Sayers RD. A meta-analysis of 50 years of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. British Journal of Surgery. 2002;89(6):714-30.

[53] Criado FJ. The EVAR Landscape in 2011: A status report on AAA therapy. Endovascular Today. 2011;3:40-58.

[54] Criado FJ. EVAR at 20: The unfolding of a revolutionary new technique that changed everything. J Endovasc Ther. 2010;17:789-96.

[55] Hendriks Johanna M, van Dijk Lukas C, van Sambeek Marc RHM. Indications for

endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysms treatment. Interventional Cardiology.

2006;1(1):63-64.

[56] Volodos NL, Shekhanin VE, Karpovich IP, et al. A self-fixing synthetic blood vessel endoprosthesis (in Russian). Vestn Khir Im I I Grek. 1986;137:123-5.

[57] Lazarus HM. Intraluminal graft device, system and method. US patent 4,787,899 1988.

[58] Balko A, Piasecki GJ, Shah DM, et al. Transluminal placement of intraluminal polyurethane prosthesis for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Surg Res. 1986;40:305-9.

[59] Lawrence-Brown M, Hartley D, MacSweeney ST et al. The Perth endoluminal bifurcated graft system—development and early experience. Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;4:706–12.

[60] White GH, Yu W, May J, Stephen MS, Waugh RC. A new nonstented balloon-expandable graft for straight or bifurcated endoluminal bypass. J Endovasc Surg. 1994;1:16-24.

[61] May J, White GH, Yu W, Waugh RC, McGahan T, Stephen MS, Harris JP. Endoluminal grafting of abdominal aortic aneurysms: cause of failure and their prevention. J Endovasc Surg. 1994;1:44-52.

[62] May J, White GH, Yu W, Ly CN, Waugh R, Stephen MS, Arulchelvam M, Harris JP. Concurrent comparison of endoluminal versus open repair in the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms: analysis of 303 patients by life table method. J Vasc Surg. 1998;27(2):213-20.

[63] Omran R. Abul-Khouodud Intervention for Peripheral Vascular Disease Endovascular AAA Repair: Conduit Challenges. J Invasive Cardiol. 2000;12(4).

[64] West CA, Noel AA, Bower TC, et al. Factors affecting outcomes of open surgical repair of pararenal aortic aneurysms: A 10-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:921–7.

[65] The EVAR trial participants. EVAR-2 (EndoVascular Aneurysm Repair): EVAR in patients unfit for open repair. Lancet. 2005;365:2187-92.

Introduction

Introduction